PI: Dr Catherine Quirk

The vast archive of actress, novelist, campaigner, and playwright Elizabeth Robins includes a document titled “Statement about the accuracy of Elizabeth Robins’ account of herself,” dated 16 March 1895. The piece formed part of the will Robins created that year, and details her reliance on misdirection to create her many off-stage selves.

The majority of actresses who write autobiographical accounts claim, or at least imply, that their memoirs are the absolute truth. Robins, in contrast, states that she “must content [herself] with trying to warn [her] relations and [her] friends that they will not find [her]or any explanation of [her] in any one’s description or in any letter or diary of [her] own.” Robins has “partly deliberately and partly unconsciously ‘cooked [her] accounts,’” replicating the silences she chronicles elsewhere in her writing as central to her on-stage performance theory.

Throughout the nineteenth century, actors, playwrights, managers, and critics developed new methods of on-stage characterization. Formal declamation encountered melodramatic gesture and pantomime, which in turn gave way by the final decades of the century to the rise of theatrical Naturalism. But we no longer have access to the performances that relied on and created these various methods. Instead, each actor’s performance technique must be pieced together into cohesive theories by way of those archives that do exist: prompt books, memoirs, letters, newspaper reviews. Even modern performances, because of the necessary ephemerality of the stage (Phelan 1993; Auslander 2008), can only be recovered through traces in these other media.

Writing Performance: Actress Memoir and Performance Theory, 1830-2016 considers a representative selection of actresses from the nineteenth through 21st centuries, all of whom wrote an autobiographical account of their life on and off the stage. In each actress’s case, the specifics of their personal theories of performance are not published or recorded as such. Instead, they suggest their theories by using them elsewhere: in autobiographical practice, in the moments they choose to record in a diary or rehearsal notebook, and even in such archival items as Robins’s personal statement which on the surface have nothing whatsoever to say about the stage. Through close reading of published memoirs and archival texts I can both access each actress’s performance theories and also analyse the ways in which those theories of performance influence and reflect their lives off the stage. In doing so, I expand the canon of historical performance theory—filling the gap that currently stretches from Denis Diderot, writing in the 1770s, to Konstantin Stanislavski in the fin-de-siècle—and add the voices of women, who have been underrepresented in this field

While modern actresses tend to be treated as an intrinsic part of celebrity culture, historical actresses are often forgotten. Writing Performance illuminates the connections between the theatrical cultures of the nineteenth, twentieth, and 21st centuries by analysing how representative actresses from each period circulate their performance theories in their writing and in their off-stage lives. Each actress has a unique approach to characterization, but each records and makes use of these approaches in strikingly similar ways. The performance techniques these actresses use—onstage and off, in their writings and in their lives—can tell us a lot about how we might similarly interact with a society in which, as the field of performance studies asserts, everything is performance.

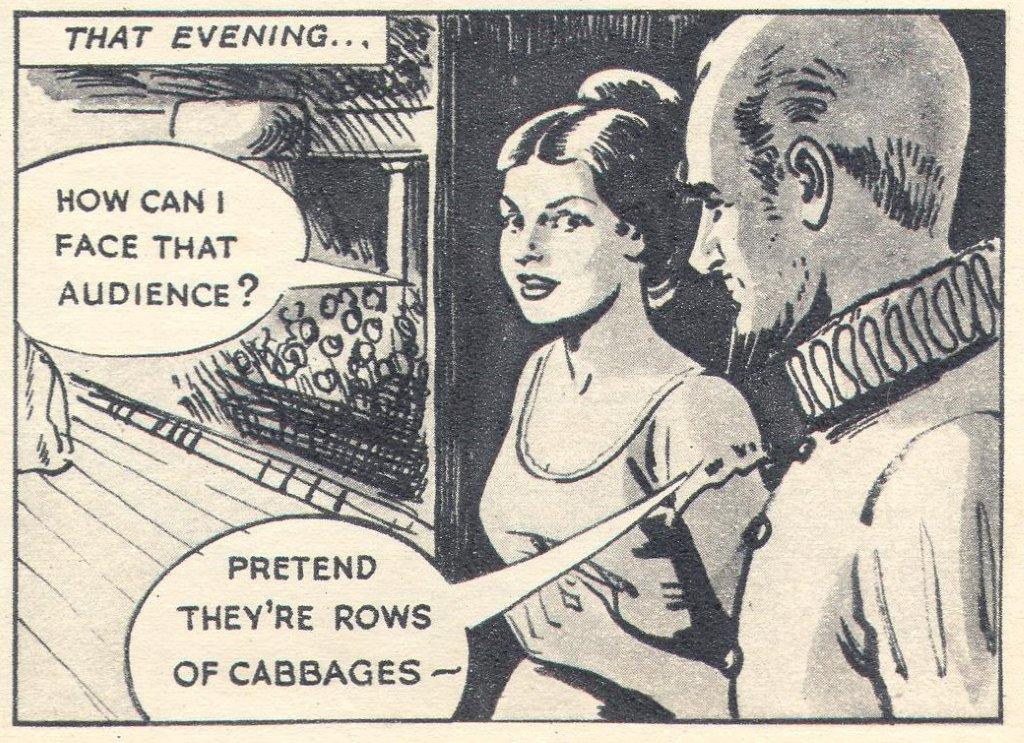

Image Credit: Fanny Kemble III, Eric Dadswell, Girl Annual 6 (1958) – from the series ‘Fanny Kemble: Crusader for Freedom’, written by Pamela Green and Kenneth Gravett