PI: Dr Sarah Fox

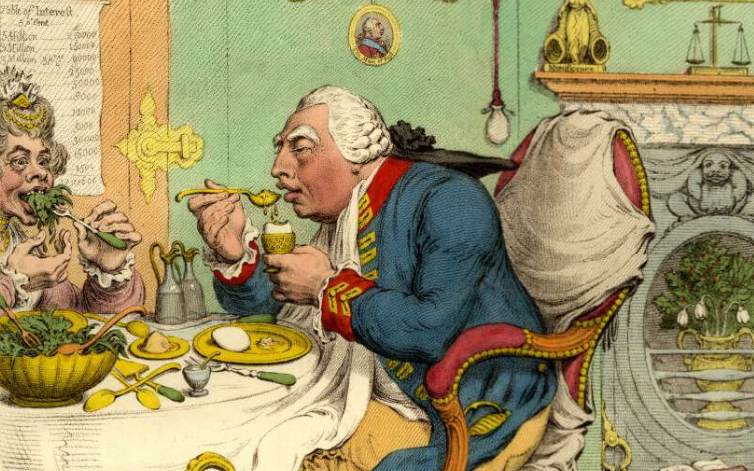

This project uses food to explore cultural influence, class, health, gender and nationality during the reign of George III. Using a dataset compiled of almost 50,000 dishes, we ask not just what was on British tables in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but what those dishes can tell us about Britishness in the first age of nationalism.

Our dataset has been built using two volumes from the Georgian royal kitchens:

- The ‘Kew Ledger’ (1788-1801), held at the National Archives and detailing the food served daily at Kew, the occasional and convalescent home of King George III

- The ‘Menu Book at Carlton House’ (1812-1813), part of the Royal Collection, and detailing the dishes served to the Prince Regent over a single calendar year

These ledgers provide details of what was served and to whom at these royal residences. In the period between 1788 and 1801, the kitchen at Kew was active on 410 days, serving 22,655 dishes to more than fifty distinct groups of eaters. The Carlton House volume provides a snapshot of a single year in the culinary life of the Prince Regent. The kitchen was active almost every day during which time the Prince’s cooks served 17,703 dishes to more than 40 individual groups of diners, with nearly half of those dishes destined for the Prince himself.

The ledgers do not just tell us about the Kings’ Dinners. Everyone in the employ of the palace was fed by the kitchen every day that they were in residence. Each was allocated food befitting their station and cultural identity, and thanks to these meticulously well-documented records that have never before been used in a systematic cultural history, we know exactly what they were served – in some cases down to the bread roll. While this group excluded the very poor, the members of these households represent a cross-section of late eighteenth-century British society, from labourers to aristocrats. By modelling these tens of thousands of dishes across season, class, age, gender, nationality, and medical status, we’ve been able to build a view of household rhythms at multiple resolutions that allow us to challenge our existing understandings of daily life and its connection to wider cultural performance. This data is invaluable to understanding the different members of the royal households, from the King and Queen, down to their housemaids. It shows us how they lived publicly and privately, how social rank affected the food that you ate, and the way physicians viewed the connection between health and food. More than that though, this information helps us to think about how ingredients, flavours, and cooking methods from Britain and across the globe, came together during a time when British identity was being defined at the dinner table.