The Edge Hill approach to mentoring trainee teachers

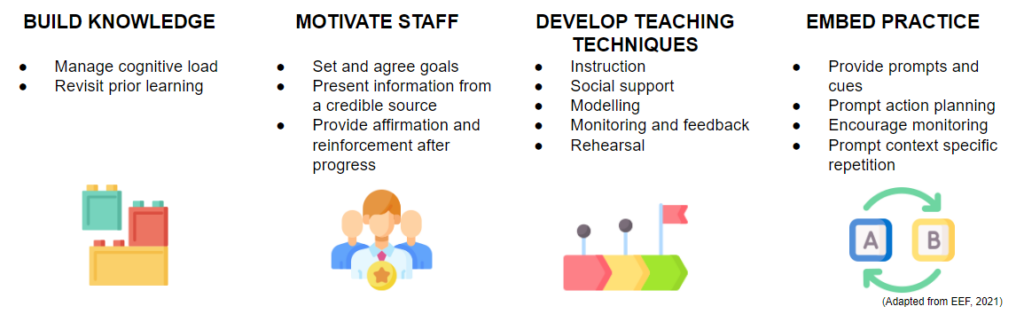

Recent research, What are the Characteristics of Effective Teacher Professional Development (Sims et al., 2021) identifies clusters of ‘mechanisms’ that are the ‘active ingredients’ in effective professional development. These mechanisms include;

- Managing cognitive load

- Revisiting prior learning

- Setting and agreeing goals

- Presenting information from a credible source

- Providing affirmation and reinforcement after progress

- Instruction

- Practical social support

- Modelling

- Monitoring and feedback

- Rehearsal

- Providing prompts and cues

- Prompting action planning

- Encouraging self-monitoring

- Prompting context specific recognition.

Programmes which incorporate at least one possible mechanism for each aim are effective, and the more mechanisms included, the greater the possible impact. In addition, Sims et. al (ibid) cite existing research which suggests that ‘one-off’ professional development events are ineffective. Moreover, there is little evidence to suggest that the length of the professional development has impact, instead professional development should be organised in such a way that key learning is revisited and that professionals have repeated opportunity to practice what they have learnt.

Such research has been adopted by the EEF (2021) to map the elements of effective professional development design into four key areas;

These characteristics map onto the coaching activities which underpins the Edge Hill approach to mentoring trainee teachers.

QUIZ

The Edge Hill ITE weekly curriculum

Being familiar with and able to support the EHU Curriculum for a given week and knowing the context in which a trainee’s professional development for that week is taking place are fundamental to the role of an effective mentor. The carefully sequenced curriculum has been designed to manage cognitive load, to ensure students receive the appropriate instruction at the appropriate time in their ITE journey and connects university-based teaching and placement experience. This enables you as a mentor to identify what students can be expected to know and therefore what they should have opportunities to practise in each week of the placement experience.

Such an approach, informed by instructional coaching, moves mentoring away from providing generic strengths or areas for development (often phrased as ‘what went well’ or ‘even better if’) and instead towards an engaged, continuous, dialogue with the trainee in which the trainee is mentored through their sequential curriculum by observing, practicing, and receiving feedback on the component skills which build to the complex composite understanding required for those who teach in their subject.

QUIZ

Read through the two case studies below. Reflect and note on the differences between the two approaches to mentoring. Which do you feel best reflects the EHU approach to mentoring? Try to link the two examples to some of the guidance and research you’ve already looked at as part of this unit.

Case study one: Mentoring a trainee training to teach in the Primary 5-11 phase

Mentor: Thanks for letting me observe today. Sorry it was a bit last minute! So, how did you feel it went? What do you think went well?

Trainee: I think it was ok. I thought my transitions were better. They were moving from the carpet to their tables quite a bit at the start and this seemed to be fine I thought. Behaviour was ok, especially for this class.

Mentor: Yes, I agree I thought that worked well. You had one or two who didn’t want to work in the groups you put them in though. That can be tricky can’t it? Maybe think about your groupings next time?

Trainee: Yes, good point.

Mentor: Ok, what else what went well? I thought your subject knowledge had improved. Is this something you’ve been working on?

Trainee: Yes, I did a bit of History in my degree but I wasn’t necessarily familiar with the topic, so I just had a look online and found some good resources. They seemed to work well.

Mentor: Great work, we’ll tick that target off. Ok so in terms of areas to work on I would think about your questioning a bit more. It was a bit unclear sometimes who you were targeting with your questioning, not sure if you had a plan for that or not. Also, this is quite a mixed class and I’m not sure some of them met the outcomes you set. Maybe next time just change up your resources a bit and maybe have an outcome for the low attaining pupils to meet?

Trainee: Yes, sounds like a good idea thanks.

Case study two: Mentoring a trainee training to teach in the Secondary RE 11-16 phase

Mentor: Thanks for letting me observe today. When we met earlier in the week, we said this would be a good lesson for you to practise your questioning and to focus on how this can help with misconceptions.

Trainee: Yes, and after seeing you with your class the other day and looking at the reading for this week, I went back to my plan and changed some aspects so I can trial some of the things I had seen you do with your class. For example, I noticed that every time you ask a question, you ask them “why do you think that?” and this seemed a good way to get them to unpick their thinking. I thought this would be good for allowing me to see where their misconceptions had come from.

Mentor: Yes, you’re right that’s a good point. It’s about the metacognition, getting them to think about their thinking which we looked at the other week. How else do you think that strategy can work well, especially if you’re trying to pick up misconceptions?

Trainee: I suppose if you are getting them to verbalise their thoughts, then they might realise themselves that something isn’t right? Or maybe another learner might have the same idea as them and it would help them too?

Mentor: That’s a great point, I totally agree. Try to start to link what you are learning about in one context, like when we looked at metacognition, and link it to what you’re doing now with questioning. It will help you to embed and reinforce what you’ve already done.

Trainee: Yes, thanks I will.

Mentor: Do you feel the strategy worked well?

Trainee: I think so, although it’s difficult to know how many questions to ask because you don’t want to spend too much time on it and then your pace slows down.

Mentor: True. Maybe there is a different way to do the questioning? It doesn’t always have to be done by you.

Trainee: Ah right ok. Yes, I suppose maybe they could question each other or do something in pairs about justifying their answer? Not sure I’ve done much pair work.

Mentor: I think that’s a great idea and looking at how you can use collaborative work, like pairs, for assessment tasks is coming up on your curriculum in a few weeks. Some colleagues are great at pair work and do it all the time, so how about I arrange for you to go and do a bit of observation of them when we come to that part of your curriculum? We can also have a look in the school CPD folder for any research or readings which will be of use. We can set it as a target in your meeting next week.

Trainee: That sounds great thanks.

Reflections

What did you think? What did you note about the two very different approaches to mentoring? Some of the differences you may have seen include:

- The mentoring style: In case study one, the mentor does the majority of the talking and this is focussed on the trainee’s generic strengths and areas of development in the lesson. There is no agreed focus and very little use of prompts to get the trainee thinking. By contrast, the mentor in case study two has a very clear focus for the feedback and has linked this to the curriculum for that week. They make good use of prompts to elicit understanding from the trainee and the dialogue is much more ‘balanced’ between the pair with the mentor reaffirming the trainee’s reflections, prompting their thinking, and reinforcing key learning. Thus, the mentoring is much more effective and the trainee gets much more information and guidance out of the feedback.

- The use of the curriculum: In comparison to the mentor in the first case study, the mentor in case study two is very familiar with the curriculum for the trainee and knows how the learning for this week (questioning) links to previous and future learning. This enables them to guide the trainee to revisit key learning and to embed what they have learnt previously (about metacognition). At the outset of the feedback, the mentor revisits the purpose of the lesson observation and it’s clear that the mentor and trainee have previously identified this lesson as a good opportunity to practice and receive feedback on a specific component skill (questioning). The trainee has also been provided with an opportunity observe their mentor, as the expert, prior to ‘having a go’ themselves. Compared to this, the mentor from case study one makes no reference to the curriculum and does not have a clear idea of where the trainee should be at, at this point in their ITE. Moreover, it is not clear if this observation has been agreed in advance or what skill(s) the trainee is practising or should be receiving feedback on. This makes the mentoring less effective, and this is reflected in the quality of the feedback the trainee receives or how this may assist with next steps. Moreover, mentor two is familiar with the pertinent research in this area. In contrast, mentor one gives inaccurate advice about artificially creating different resources for different learners and lowering expectations for low attaining learners. Neither of these suggestions is in line with the current DfE guidance for trainee teachers (DfE, 2021).

- Identifying opportunities for development: A key feature of effective mentoring is identifying opportunities for trainees to dialogue, observe, practice, and/or receive feedback on the component skills set out in their EHU ITE curriculum. This enables the trainee to build their understanding towards a complex composite understanding as they make progress through their ITE. In case study one, the mentor provides feedback on the ‘areas for development’, but there is no indication of why or how these areas will assist with the trainee’s progression and no discussion about how the trainee could gain the experience or skills required. As a result, the trainee may be left with the feedback from the mentor but very little idea how to act on this feedback, why it has been identified as an area for development, or be given advice which is inconsistent with current DfE expectations. In comparison, the exchange between mentor and trainee in case study two is a good example of effective mentoring. The mentoring has prompted the trainee to identify ways in which her use of questioning could be developed (by using more peer feedback), has linked this to future learning (on collaborative assessment), has identified an opportunity for the trainee to observe an expert in this area (another colleague), and will support this with credible sources (using research from the school CPD folder).

QUIZ