I Could Never Go Vegan: Q&A after the screening at FACT picture house (Liverpool)

Bianca Friedman (CfHAS PhD researcher)

Saturday 27th April, FACT picture house, Liverpool. Just a handful of weeks after the London world premiere (10th April) and some promotional screenings, Thomas Pickering’s new documentary I Could Never Go Vegan landed on the Mersey shores. The documentary accompanies the audience through an accurately documented and systematic deconstruction of the main arguments against veganism, comments made by non-vegan people and the most common justifications picked by people who claim “I could never go vegan”. The film’s diversified aesthetic choices and the overall energetic narrative tone make the topic accessible to audiences. The core arguments are discussed seriously, with the support of both an impressive amount of data derived from careful consultation of scientific literature, and a variety of experts, from researchers to doctors, from athletes to activists, from university professors to chefs, from writers to CEOs. This array of different perspectives constitutes a very much needed choral response to many of the most common observations that vegan people hear since the very beginning of their vegan journey.

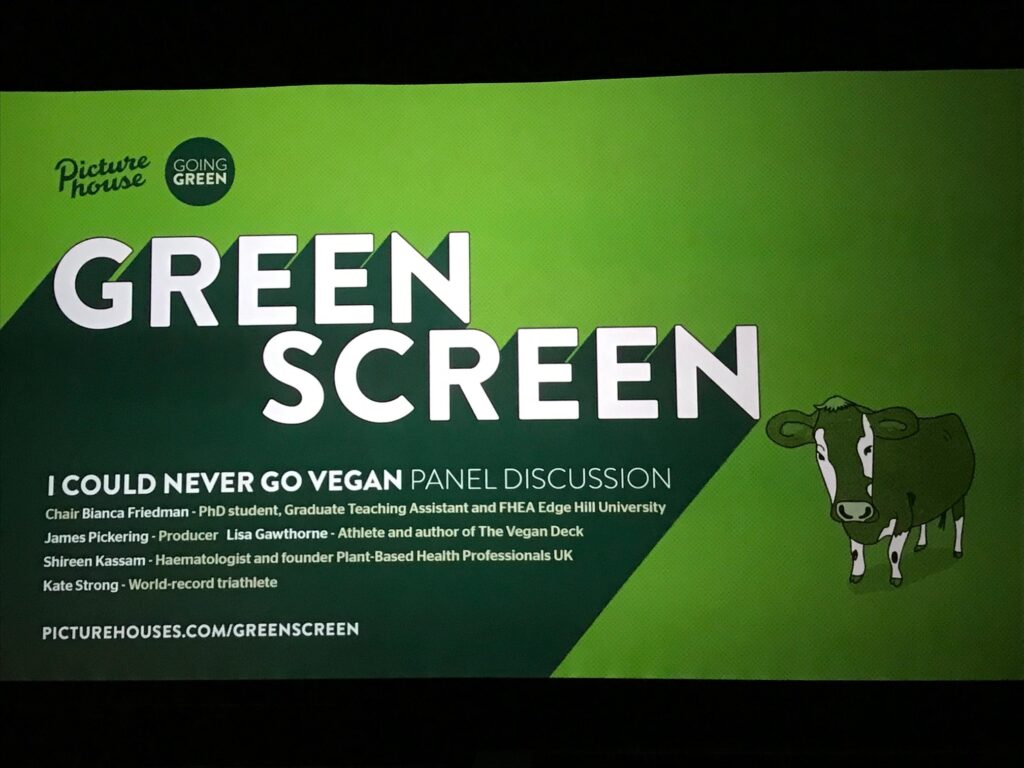

The FACT special screening, as part of the Picturehouse Green Screen series of shows, was followed by a Q&A with James Pickering (producer of the film), Shireen Kassam (haematologist and founder of Plant-Based Health Professionals UK, member of the film cast), Kate Strong (world-record athlete, member of the film cast) and Lisa Gawthorne (athlete and author of The Vegan Deck). Chairing the panel offered the opportunity to ask a couple of questions which were enthusiastically answered by all the members of the panel, before the floor was opened to the audience. What follows is a record of the first part of this lively discussion.

(Trigger warning: this article contains references to practices that may cause distress)

Bianca Friedman (BF): At the beginning of the film, you mention that veganism is rising in numbers, and you provide figures to demonstrate this point. This made me think about the growing quantity of documentaries and films that either directly or indirectly encourage people to adopt a vegan diet (such as, for instance, Cowspiracy, Seaspiracy, Okja and other small-screen and big-screen productions). So, my twofold question is: can audio-visual productions (both documentary and fictional) foster the rise of veganism? And how challenging is it to combine the impressive amount of data that you refer to with an accessible and captivating format and aesthetics?

James Pickering (JP): Interestingly, when Tom [Pickering] called me four year ago and asked me to produce this film, we didn’t really know what it was at that time. I had seen films such as Cowspiracy, The Game Changers, and other ones. There are some really powerful films in this field, and a lot of them focus on either animal welfare, environmental crisis, health issues. I thought it’d funny to flip the kind of formula and look at the reasons that you hear about why people would not go vegan. So, at that time I said to Tom, let’s look at the five/six biggest reasons people wouldn’t go vegan and a few weeks into the journey, I said “that’s boring, let’s look at all reasons”. Which was challenging itself, so, four year later it is why it took so long to release the film. And then, to include all that data it became problematic how to fit it into a cohesive narrative. I absolutely do think that filmmaking, TV shows and documentaries can impact change. I am really fascinated by the impact of documentaries in general, whatever that may be. And I think that they can push for change: I know so many people who have seen Earthlings, The Game Changers or Cowspiracy and that that has led them to think about reducing their animal product intake, or, as Shireen says in the film, whatever people feel that they can do. It really is about what area people care about. People often think it might be the environmental crisis: if you’ve got a young son or daughter that might be the thing that makes you want to reduce your animal intake, because you’re thinking about their futures, it might be the welfare side of it, it might be the health side of it, it might be that you want to focus on the athletic side of it. So, it really is about whatever relates to you the closest to reduce your animal product intake.

Shireen Kassam (SK): Brilliant film, of course, but I think it shows us how doctors and scientists could do so much better with our patients if we were better at storytelling, because it is not enough just to know the facts. You know, scientists have been telling us for decades that the planet is warming, doctors know that the food that we eat is the key impacting our patients’ lives, but it is really hard to support people to change behaviours and we really need to understand what people’s motivations are, as you say James, and make them relevant to their lives. And I think storytelling is one really powerful way of achieving social change and we know this from history, so thank you that you’ve done it for the vegan story as well now, James.

Kate Strong (KS): It’s the first time I have seen the movie, so thank you for that gift. I’m actually opposite in that I don’t watch vegan movies, I’ve been vegan for 10 years and I don’t need convincing. My journey, or my narrative is actually to stay in the grey, stay in the confusion… There’s narrative to prove anyone’s right: as we all know, there’s fake data, there’s fake information out there. So, what I am discovering a lot is actually that it is useful to stay with people who eat burgers, who kill animals, who eat meat because they think it is more environmental, because I have to stay in the question, not coming from a fixed point of knowing that I am right. It is not meant to mean that I am not right, it just means that I close the conversation down by not staying curious. So, however hard it is, my personal journey is to actually do the opposite, which is to visit places where people still ask me where I get my proteins form, why I do not eat meat, why I do not recycle plastic instead of not having lamb. I’m actually finding that my journey is to stay in the opposition, not to come out with all the reasons why, but to understand why they still stand where they are.

Lisa Gawthorne (LG): That’s very interesting, I can contrast to that, I am a walking billboard for veganism! I’ve been vegan for 21 years, previous to that I was veggie since age 6. Coming back to the effects that these kinds of documentaries have, I think the effect is unbelievable, it is so powerful. From a personal point of view, I find it so much easier to be able to direct people to documentaries rather than send them loads of links to medical journal references or the latest article that’s been printed somewhere. It’s brilliant because it encapsulates so much data. I can see four years of field work, but it feels like forty years for the amount of detail that has gone in: so, it’s unbelievable on that point! And I’ve got first-hand experience of family and friends turning vegan over the last few years. My boyfriend who’s in the audience tonight turned vegan the second The Game Changers finished: when the credits went up he was “that’s it, I’m done”, he turned vegan overnight and never looked back and he’s pushing personal records in the gym with regards to being a lot stronger. And that’s where I am from an athletic point of view. I am out there and doing things all the time and I carry a lot of pro-vegan messages on the outfits that I wear and I like to do that purely because it gets people to come in over, to have questions and it gives me an opportunity to then direct people to brilliant films like this!

KS: If I may add to that, I do the exact opposite, I do not even mention my veganism, because when they come to me and ask questions I’m: “It should be so obvious that I am vegan, we shouldn’t even have this conversation! Why are we discussing my food? Of course I am vegan, because I am an élite athlete! So, can we just move on to my training?”.

LG: I love it!

BF: Thank you for your answers, and it is actually a good link for my second question. What I really liked about your film is that it connects individual stories with bigger questions, that is environmental, ethical and social issues. You therefore connect the private act of eating with a political dimension, which is great and it really works in terms of storytelling, because it accounts for both the private and the public dimensions. However, thinking about putting this film together and especially about the heartbreaking scenes shot in slaughterhouses and factory farms, I couldn’t help but ask myself: how challenging is it, both on the psychological and on the practical level, to film in these contexts? How do you cope with these images, especially you as a producer and all the people who worked on the editing, which obviously takes time and implies seeing these images over and over again? Can you tell us a little bit about this? I know it’s sensible stuff, but I guess it was part of the creative process.

JP: No, absolutely. So, Tom and I and an undercover investigative journalist went undercover to a big farm which we left completely anonymous, as it wasn’t about pointing out where the big farm was, it was about looking at the system: we wanted to see what the “normal” standards looked like. Tom found it really difficult. For the editing process, with regards to the slaughterhouse, I went through the footage for Tom, who was the editor and director while I’ve written and produced it, because he found it really difficult. And it was interesting in the post-production phase because the person who coloured the film was a meat-eater when he started the project and then by the end went vegan: it was just from colour-grading that footage. We did find it interesting and we came to talk about it afterwards and it clearly affected him. Tom did the pig farm and it is really difficult to articulate what it’s like when you’re there: you go through the phases, the smells the things you see, it’s… They’re never going to want people to see that, that’s just how it is. But it’s really difficult, unless you’ve experienced it, to articulate, because the words I say won’t do it justice, maybe the visuals did. The table sequence at the end, where Tom lays out the photos, before I started the screenplay, after we’d shot all the footage, we knew it was going to build up to that bit. I kind of wanted to show how every section was linked, you know, how the environmental side and the animal welfare are interlinked, so it was all building to that point. So, we knew we were going to have to show some welfare footage, but we knew that nobody really wants to see it. We wanted to have an accessible documentary that mainstream audiences would watch, with humour in it, but we couldn’t ignore the animal welfare side of it. We discussed briefly at the start about animating some of the sequences, but we didn’t think that was fair to the animals and also to the people who worked in the industry, because we really wanted to talk to those as well: Doug and Alice who were in it, they are clearly still going through it and have been massively affected from working in the industry, and we wanted to tell their story too. So, we’ve got this 3 to 4-minutes sequence in there, hopefully it’s just about the right balance for people to see what it is like within the industry. It was challenging, but, you know, we couldn’t ignore it and we had to put it in there.

KS: I’m really surprised it was only 4 minutes, it felt like 20. I was sitting there in tears, I can’t believe it was only 4 minutes.

JP: I think the welfare section is maybe longer than 4 minutes. In terms of the actual footage it is a longer section, but in terms of what it is actually shown we had to cut it. There were a couple of bits where we learnt from. Before making the documentary, I actually didn’t know about how piglets were killed, which is a horrible, horrible sequence. And when I learned about that and hearing this talked about so candidly, of just how normal and acceptable is the legal way to kill a pig, I said “we have to show that”. And we shoot it from a distance, so it’s not about showing any graphic gore, I just couldn’t believe that that is how they kill piglets, I was baffled and I thought we had to show it.

KS: I think you captured it immensely powerfully. I am just very surprised by how impactful it was, in the short time it was on the screen. Just out of curiosity, to bring it to the room, hands up who’s actually been to a farm or slaughterhouse or anything like that? [few people lift their hands] I’ve been to one as well, I only went to a salmon farm, and it’s something that never leaves you. So, yeah, bringing it to the screen you’ve done immensely well, because I think more people need the conscious awareness to make a decision, that’s all we want: if you want to eat this, this is the consequence, that’s all. No judgement, but this is what’s happening thanks to you, thanks to your choices.

LG: I was exactly like Kate during that scene, and probably most of the audience. I think anyone with a heart can say that that is upsetting. No one wants to watch that, it’s absolutely heart-breaking and it stays with you, it really does, but sometimes you’ve got to just see a little bit of it, so that it gives you that kind of energy to believe “right, OK, I know that if all the people see this, it will hopefully give them that kind of “why am I doing this? Because, well, what I am eating, let’s boil it down, involves death, torture, pain, and that can’t be good for the soul anyway to be consuming those negative things”, not to mention, obviously the unfairness of the whole thing. But I thought that the way it was handled was really good. And I was like Kate, it felt like half an hour, just because I’m very sensitive to that kind of thing as well.

Watch the trailer of I Could Never Go Vegan:

L-R: Lisa Gawthorne (vegan athlete), Bianca Friedman, James Pickering (producer), Dr Shireen Kassam (founder Plant-Based Health Professionals), Kate Strong (vegan athlete).