Ambient Television

Aoibhinn McGoldrick

This year, we are showcasing some work from our best students, including Aoibhinn who looked into the role of ambient television for viewers today for her podcast. Please enjoy.

Is Privatising Channel 4 a Good Idea? The answer is simple: no.

Elke Weissmann

On Monday, 4 April 2022, Nadine Dorries tweeted: ‘I have come to the conclusion that government ownership is holding Channel 4 back from competing against streaming giants like Netflix and Amazon […]. I will seek to reinvest the proceeds of the sale into levelling up the creative sector, putting money into independent production and creative skills in priority parts of the country – delivering a creative dividend for all’.

Her words were met with disbelief and disappointment. First of all, it is unrealistic to expect a UK-based national broadcaster to be able to compete with streaming giants that operate in most of the world. Second, the channel isn’t government owned, it is publicly owned: it is not the government that owns it (like the state broadcaster CCTV in China for example), but the public – us. In part, the public response came as a result of her performance in the Digital, Culture, Media and Sports Select Committee in November 2021 where she had to be corrected on how Channel 4 was funded. Surely, someone who makes such a fundamental error and is informed about the fact that Channel 4 does not receive a licence fee or any other public funds would see that privatising it, i.e. selling it off wouldn’t make any sense? For those of us who either study or work in some other way with or on Channel 4, privatising it is non-sensical.

Channel 4 is a commercially funded public service broadcaster. It is financed by the advertising it shows and is bound by a remit of innovation, experimentation and championing of unheard voices amongst other public purposes. Any money it makes goes back into new commissions. It commissions all its content from independent production companies and is indeed the reason why the UK has such a thriving film and television industry: its model, developed in the 1980s, was part-adopted, through legislation, by the BBC and ITV as well.

For my research, I speak to people who work in the independent sector in the UK, most recently with people in Wales. Welsh drama, you will have noticed, has become quite successful, both nationally and internationally. Hinterland/Y Gwyll (2013-2016) was sold into over 100 territories and attracted more audiences in Germany (4.5 million) than in the UK (where it was shown on S4C and BBC 4). Channel 4 has recently ventured into a similar co-production with S4C and the resulting drama will be shown on Channel 4 later in the year. What this highlights is that Channel 4 is already doing what Nadine Dorries wants to see: it is putting money into priority parts in the UK – in this case Wales, but it is also doing it elsewhere. Indeed, it is Channel 4’s strategy of commissioning everything that has allowed independent production companies to emerge in different parts of the country, including in Manchester where Red Productions is situated quite deliberately, precisely because it wanted to tackle the London-centrism of the broadcasters, as did Colin McKeown and Jimmy McGovern who work from Kirkdale in Liverpool, an area which definitely counts as a priority area in need of ‘levelling up’ or at least some form of financial support. Colin McKeown got his first producing role on Brookside for Channel 4. Red Productions, led by Nicola Shindler, got their break with Queer as Folk, another Channel 4 commission. As a result, the independent producers I know are similarly dismayed as me. Steve Smith from Picture Zero Productions for example tweeted ‘Can’t help but feel the government are making a big mistake. Very disappointing and a big blow to the independent production sector’.

As my research into the Welsh television industry indicates, there are other ways of supporting the creative industries so that they can thrive in all parts of the UK. If perhaps too much of the media are still based in the South-East for England, then Wales has a problem with being too centred in Cardiff. But there, the devolved government, producers and broadcasters, including the BBC and S4C have recognised the need to diversify and have worked with the Centre for the Study of the Media and Culture in Small Nations at the University of South Wales to examine what could be done to diversify production locations. They came up with a list of recommendations which include the need for financial incentives to move productions into different regions, which both tourist boards and the Welsh government try to offer. In addition, new infrastructure is needed, and again this has led to investment in studio spaces in northern Wales, a strategy emulated in Liverpool where it is the local government who is part-financing the Littlewoods Studio Complex development. Finally, the Centre recommended close working relationships with schools, colleges and universities that already provide the skills training that Nadine Dorries believes the sale of Channel 4 would enable.

What the case of Wales makes evident, then, is that the joint effort of government, public service broadcasters which are in public hands, production companies and universities can lead to a thriving and diversified creative industry. Such an evidence-based approach looks sensible and sensical and in addition has the buy-in from all involved, including Welsh audiences who, through watching so much of it on the IPlayer, have helped programmes such as Keeping Faith/Un Bore Mercher (S4C and BBC, 2017-2020) to find mass-audiences way beyond Wales.

A Television Studies Research Group – Why we, unfortunately, need one now

Elke Weissmann

As promised, in this second blog, I wanted to give a bit of an insight into why we do, unfortunately, need a new Television Studies Research Group. And there isn’t just one reason for this, but rather a plethora of interweaving conditions that affect the teaching, researching and making of television.

Let’s start with the teaching which at Edge Hill University includes quite a bit of practice. Teaching media studies and television, particularly when it has a practical component, has become a bit more difficult again. The Conservative Government have made it abundantly clear that it favours STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) subjects over others. Whilst there is no question that these subjects form the basis of a great number of jobs, so do subjects in the arts and humanities. What differentiates them, is that some of them are perceived as more masculine and hence come with good remuneration, while others are perceived as more feminine and thus, as so much feminine-coded work, superfluous, leisure-related or non-remunerable due to its domestic nature. With its over-emphasis on quantity as measure of success (amongst others by emphasising graduate earnings in documents such as the Augur Report), the government therefore largely embraces existing social value hierarchies that disadvantage anything connected to the feminine. This goes along with recommendations to cut funding for arts subjects, which many unions, recognising the complexity of the world of work and its reliance on the intersection of traditional STEM-derived jobs and arts and humanities derived jobs, have tried to oppose.

Television, in many ways, is typical for these intersections: it is part of the creative industries and thus operates within the contexts of the arts. It has produced art and stories that we connect to. But it is also an incredibly successful business which brings significant revenue into the country, amongst others by selling content across the world and/or helping to remake television originally produced here in other countries. One key market was the European one where British productions were much priced not just for their quality, but also because they could be classed as ‘domestic’ productions as long as we were still in the European Union. The BBC, for example, now makes approx. 1/3 of its revenue from other sources than the licence fee, much of it from international sales. Another effect of Brexit, then, is that the money to be made for television is now likely to decline. This will reduce the ‘value’ not just in terms of monetary value, but also hierarchical status, of television. Thus, its potential kudos in a traditionally gendered hierarchy that it derives from its ability to make money is lost on the basis of another Conservative policy. But television also relies on the other arts in order to be what it is, and the reduction of the other fields will inevitably impoverish it further, thus also creating less interesting fare.

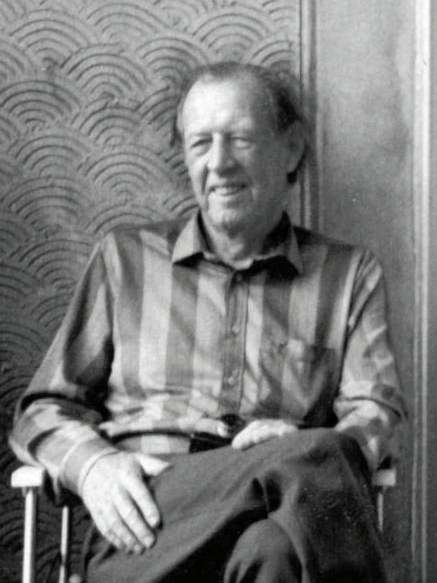

But educational policy in regard to graduate earnings isn’t the only problem for teaching television. Here, at Edge Hill University, many of our students come to us because film and television have been subjects which they have discovered in school and college as spaces where they can express themselves. Traditional forms of expression, primarily literature, doesn’t suit all of them well because they struggle either as a result of an undiagnosed learning disability or because they do not recognise the medium as something that is theirs because they do not come from middle-class backgrounds were literature and high art is readily available. Television, in contrast, is. And one of the things that has always struck me is how many of my students still know, watch and love their local television (as evidenced by the number of essays I get on The Inbetweeners, Love Island etc.). Many of them come through BTEC routes that give them access to media, film or television courses which they decide to continue and where television has given them the greatest chance of a career (see image below). These BTEC routes are another aspect that Augur reported on and recommended for change. Students like mine – coming from working- or lower-middle-class backgrounds – should consider routes that will apparently give them greater financial success, Augur seems to suggest, by emphasising apprenticeships. This is galling for two reasons: not only does it disadvantage the disadvantaged further by reducing career opportunities, but it will also solidify the obvious imbalances that our industry is struggling with in terms of becoming more inclusive. In addition, it means that television – an incredibly successful industry in the UK – appears yet again as non-worthy of the pursuit of a career for my, or indeed any, students. This will probably mean that we see fewer instances such as the below:

As the above indicates, the current political climate operates with traditionally gendered and classed (and of course raced) hierarchies that severely affect my ability to teach television and for the television industry to make it. I have written before about how these hierarchies also influence research, so I will end here. But this is why we need a Television Studies Research Group which is dedicated to Television Studies as a subject for these three pillars: research, teaching and production. We live in a climate of hostility. And we are here to emphasise our (and the industry’s and our students’) value.

A Television Studies Research Group – Why now?

Elke Weissmann

Do we really need a new research group dedicated to studying such an old medium?

There are two answers to this question. The first one is: unfortunately, we do. The second one is: fortunately, we do.

Over the next few weeks, we want to write a number of blogs that explains these answers. Let me start with my very personal response to the second one: fortunately, we do.

Over the last few years, something miraculous has happened at Edge Hill University: in my department, the Department of Creative Arts, I have been able to speak to colleagues and students about television. More importantly, they just understood. They have studied and researched television themselves and they too love it as much as I do. In other words, I am suddenly finding myself surrounded by lots of colleagues and students who are interested in television as television and their research is interesting and (in my eyes) really really good.

Having a group of like-minded staff and students around is quite special for a TV scholar. Our medium might look old to others, but it is still relatively young and has only been studied for some 40 years or so. Many of us date our ‘existence’ as a subject area back to Raymond Williams’s Television: Technology and Cultural Form (1974), though it would take a few more years before television studies as a subject would really come into being. Central for that was the work of feminist writers in the 1980s examining the role of soap opera. This research has inspired me a lot, particularly Ien Ang’s Watching Dallas (1982) which was the first television studies book I ever read and to which I had a really visceral response that made me want to study television differently to how I was studying it at the time.

At that time (this was my undergraduate degree in the late 1990s), I was studying Media at the University of Mannheim, Germany. Television studies as a subject then didn’t really exist in Germany. Instead, we looked at audiences as numbers: so many people watched this, so many people read newspapers, etc. Alternatively, popular media were examined with the concerned distance of the Frankfurt School. Then, one day, I sat in the library and read Ang who examined in detail what people had to say – what they really had to say about television. She saw them in the way that I experienced watching television: as something that gave meaning to me and the world around me. As something that I enjoyed tremendously, that I learnt from, but that also frustrated me at points. This is how Ang’s audience spoke, and this is what Ang took seriously. It inspired me to take television and its viewers and producers also seriously, and to recognise that when we don’t, we often speak not from a point of openness, but from a place where value is predetermined.

Now, I am surrounded by colleagues and staff who look at television with the same interest and openness and who, like Brett Mills did so brilliantly recently, question why we are sometimes blind to certain things, including how we see and conceptualise animals on television, but also why we are blind to television that conceptualise animals as beings.

So do we need a television studies research group? Yes, we do: because we finally can.